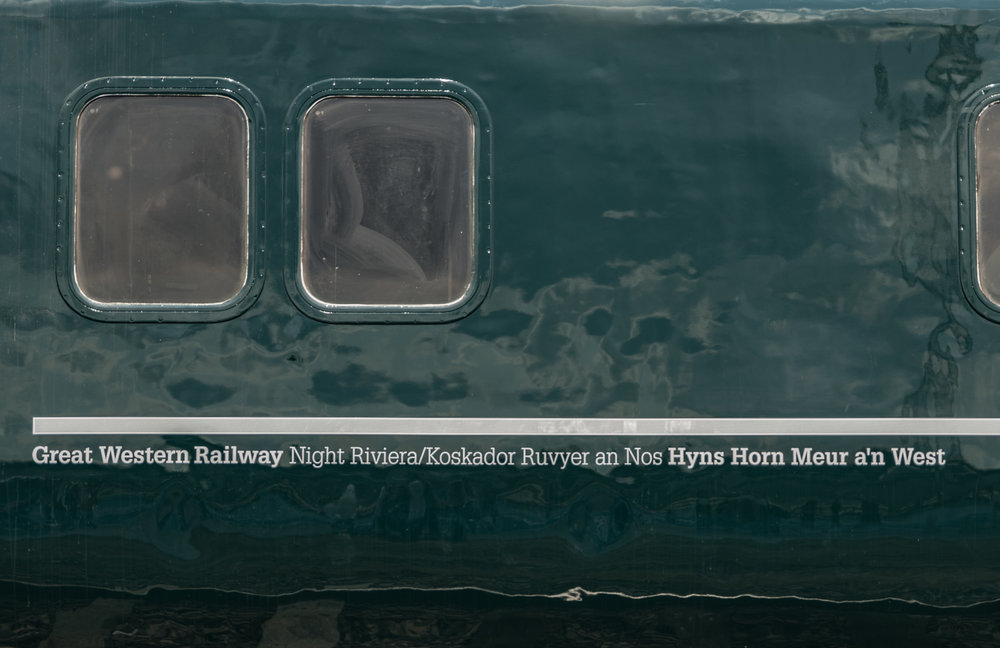

Whenever we get a visit from our German American friend, Ralf Meier, there’s bound to be a puff of steam in the air. Ralf runs the popular Trainphilos blog and is a specialist in modern railways, although he has a soft spot for the vintage steam stuff. This time, the big occasion was a visit to the last-ever Great Western Railway open day at the massive Old Oak Common Depot in West London. They’ve built a new area for the latest high-speed trains and the old site, along with surrounding derelict areas, is soon to be bulldozed in favour of a mixed development including 25,000 new homes. That effectively demonstrates the size of the old site.

18,000 Spotters

I decided to trundle along, camera in hand, because I sensed there might be more than just trains to snap. I was right. There’s nothing like a “last” of anything to draw the crowds and it was no surprise (having queued almost all the way back to Willesden Junction Station) to find that the organisers had sold 18,000 tickets at £20 each — with the profits going to charity, incidentally.

Now trainspotting is a very British institution. Boys (almost always boys) of my generation were introduced to the spotting of trains at a tender age. It was a right of passage, usually leading up to puberty and often petering out as train numbers and names began to lose out to more interesting pursuits. But not for everyone. Here were 18,000 of ‘em to prove that.

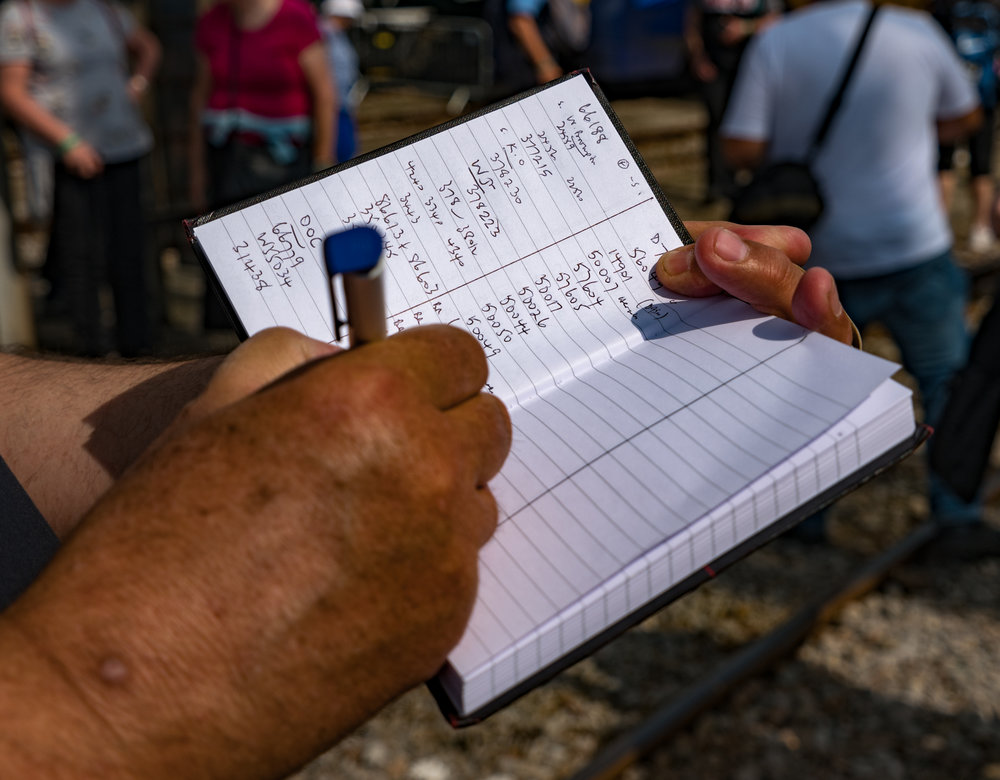

For my part, I carried around a little book filled with train numbers for several years. I would stand on station platforms scribbling down the comings and goings with one of those new-fangled biro pens. It came to be an obsession, if a short-lived obsession.

For some men (and it is largely men, from observation) fascination with railways and rail travel extends well beyond puberty. Indeed, it is a passion that never seems to wane. That little book from the early teenage years joins dozens of others on the shelf and, despite the wonders of modern technology, men can be seen clutching their books well into old age.

Below: Another number, another notebook. This is the art and heart of trainspotting; Alan Turing would have had a field day….. (click to enlarge)

It’s facile, of course, to suggest that collecting numbers is the sole objective. In fact, most train enthusiasts don’t spot at all. They take a much deeper interest in the subject and become an authority on all aspects of rail transport. Ralf, for instance, knows as much about the infrastructure as the trains; he spouts catenary and freight; bogies and engines; high-speed lines and bullet trains. He’s a veritable walking encyclopaedia of trains.

It is also too easy to dismiss single-minded enthusiasm as a trifle peculiar. It’s evident in the popular terms. In Britain train fans are know as “anoraks” from the handy waterproof garment of that name, although the terms tends to be applied to dedicated fans of most esoteric areas of life, from vintage cars to modern cameras. I have been known to be an anorak on occasion. In the USA, train enthusiasts are know as “foamers” which, to my ear, sounds somewhat more derogatory than “anorak.”

But I think such dedication is admirable. Everyone needs a passion in life and trains are as good as anything as a focus of hobby lust. I used to be like that with motor bikes; now it is cameras and photography.

It’s a man thing

With that in mind it was ordained that we should be standing in that long line of men. The really dedicated made sure to leave Mrs. Spotter back at the home depot so they could have free rein with the bogies, unruffled by any show of jealousy.

It turned out to be a jolly affair and the good weather provided every opportunity to clamber over the special display trains or take a ride in full-size or (on) miniature sets. That’s the thing about train fans. If there’s a mechanical contraption to ride, then it doesn’t matter how large or how small. It has to be ridden.

Even the thoughtfully provided funfair was dominated by the train fans. No doubt it had been introduced to keep the kids happy, but the big wheel was full of big people — mostly camera in hand, anxious to gain a bird’s eye view of the proceedings. And the Harlington Locomotive Society’s tiny steam engine groaned most of the day under the excessive load of big men of all ages, legs dangling perilously close to the track. The occasional female or child was barely tolerated. The impression, it has to be said, is that inside all men is a bunch of kids waiting to get out.

It was the vast area that made the day. Truly vast. Old Oak Common is full of history. The Great Western Railway opened the depot in 1906 as a convenient corral on the London to Bristol mainline, the first section of which had opened 68 years earlier in 1838.

The GWR — sometimes known as God’s Wonderful Railway — is synonymous with the exotic name of one of Britain’s finest engineers, Isambard Kingdom Brunel. He also built bridges, constructed ocean liners and bored tunnels, but his finest achievement was the GWR with its massive 7ft 0-1/4in wide gauge track (I always thought it was a spot 7ft but Ralf insists should accurate and I’ve added the quarter inch to placate the purists).

Brunel was a visionary who foresaw high-speed trains and mass transport. His broad gauge was considered to be “more commensurate with the mass and the velocity to be obtained.” Wheel diameter could be increased, reducing friction (at least on the straight, which constituted the bulk of the line), and the wide carriages could be built with low-mounted bodies to keep down wind resistance. But there were problems, largely in terms of the increased size of necessary infrastructure, cost and incompatibility with the ever-growing narrower standard gauge competing networks

Unpopular prejudice

Brunel lost the argument for many reasons. He was promoting the virtues of a seven-foot-wide track when popular prejudice ran to a mere 4ft 8-1/2 inches — the width between the wheels of colliery wagons in the 18th century north east of England. Standardisation was everything, and turned out to be a good thing in the end. If Issy had had his way we’d all be running around on seven-footers, but this best of systems was too expensive and Robert Stephenson, with his “narrow” standard gauge, won out. You could say Brunel’s trains were the Sony Betamax of their day.

After a process of attrition over several decades, the futuristic broad gauge was finally consigned to history on 23 May 1892. In under two days 177 route miles of main line were converted from broad to standard gauge with almost no traffic disruption. It is hard to see such slick work happening this side of the millennium.

From 1906 Old Oak Common provided maintenance facilities for the GWR and latterly has been the main facility for storage and servicing of locomotives and multiple units from Paddington Station, the railway’s London terminus. Its closure after 111 years is therefore a big event in the eyes of railway enthusiasts and they flocked to get a final glimpse of the vast historic yard. The name will live on, however, since it is a major station on the new high-speed line and an interchange with the Crossrail project linking Reading and Heathrow Airport with central London and Essex, due to open next year.

Basking

Quite a day, then. Imagine 18,000 people who know almost everything there is to know about trains, steam or otherwise. All in one place at the same time. Here was an opportunity to bask with one’s own kind, sure in the knowledge that no one would think you at all odd.

It’s a bit like camera fairs, really. And vintage car events. I often suspect these 18,000 people just change their anoraks and appear as extras at dozens of fan-type events every weekend. They do tend to look alike.

As we used to say in Lancashire, “there’s now’t so queer as folk”.

Meanwhile, Ralf is taking a very adult and critical view of things. After all, he even goes to real railway industry exhibitions such as Innotrans in Berlin. He’s a real industry expert. And he was in his element. I was just a groupie, tagging around with my camera.

To capture all this frenzy of activity I took along Leica’s SL mirrorless camera but accompanied by a couple of crop lenses from the TL system — the wonderful 11-23mm wide-angle zoom and the standard 18-56mm. The result of using a crop lens on this full-frame camera is that the picture size is reduced to only 10.3 megapixels from the full-frame 24MP. But they’re bigger pixels, just a bit like Isambard’s wide tracks, or so I tell myself.

________________

- Subscribe to Macfilos for free updates on articles as they are published

- Want to make a comment on this article but having problems?

A great set of pictures, and I’m sure a lot of rail fans would love to see them.

Thanks, Richard. It was a great day out and a perfect place to do photography.

Oh boy I sure would have liked to have gone to that, who knows I might even have taken my old Ian Allan ‘ABC Of Train Numbers’ trainspotters book, and yes I do still have it and it is dated from September 1st 1951 but a bit frayed now at 66 years old. Come to think of it maybe not as frayed as I am at 80+. Anyway thanks Mike you have made my day. Don

Dear Don,

Glad you enjoyed it. I realise I was preaching to the converter — to some extent — but I always bear in mind we have an international readership and the intricacies of British eccentricities sometimes need explaining. I don’t assume anything!

Not yet having had the pleasure of using TL lenses on the TL2 – shipping was halted the day before mine was to arrive – I have been delighted with them on the SL – and equally pleased to find that the cropped images bear up well against the TL shots. I’m certain that the larger pixels and perhaps the nature of the SL sensor help there but I have been able to crop the cropped images significantly – much like your duck in the example you posted. I shall be interested to see how they hold up against the 24mp of the TL2

It’s a very interesting question, Tony. I am very surprised by the results from the TL lenses on the SL. On pure figures, the 10.3MP, I would not have expected this.

Wonderful History! Just as an aside here in the states during civil war their were basically two sizes of gauges North had heavy large Gauge and South used lighter smaller size. When Union General Sherman made his march to the Sea they ripped up the Souths small gauge and laid new heavier tracks from industrialized North. Southern tracks were not made to withstand the weight because they were more Agriculture society cotton tobacco etc. Sherman to show his contempt for the Rebels would have his crews bend track sections around trees that they removed, hence the Civil War nick name "Sherman’s Bow Ties" was born!